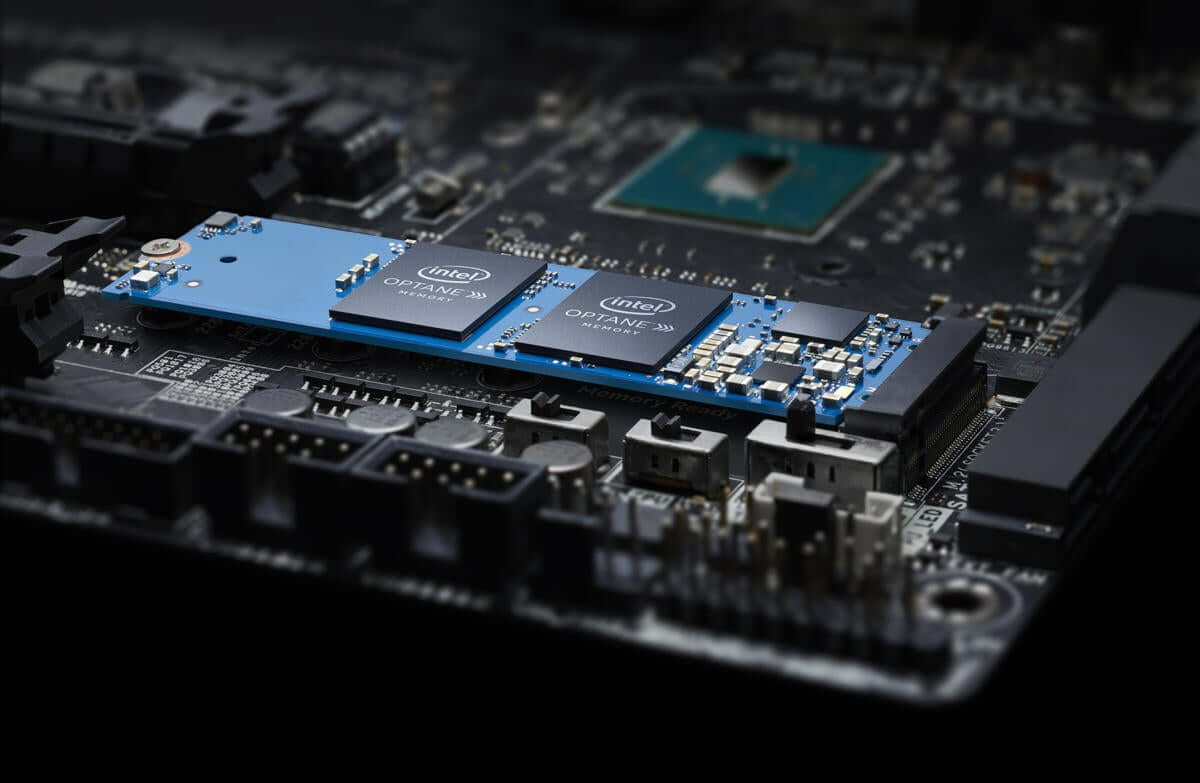

Intel’s optane memory, released last year, claims to be a new innovation in memory technology. I came across a stick of this memory in a new 2018 HP desktop that made it’s way into the shop for repairs. Immediately it struck me as odd. It’s elongated shape crammed with BGA chips was placed beside the wifi card in a PCIe Mini slot.

Intel claims this memory architecture is faster than NAND flash yet slower than DRAM, functioning as a sort of cache between the HDD or a standard SSD and RAM. This makes sense because there are obvious bottlenecks when fetching data from a slow device like an HDD. This technology will ideally increase the feed rate of data to the CPU.

In fact, Optane is basically a next-gen version of Intel’s Smart Response Technology (SRT), which used cheap, low-capacity SSDs to cache data for slower, high-capacity conventional hard drives. The difference is that Optane uses memory manufactured and sold by Intel, in conjunction with special hardware and software components on compatible motherboards.

Intel is already selling “Optane” storage drives for corporate data centers. These are closer to conventional SSDs, bringing that expensive, speedy memory right to the storage component of mission-critical servers. Right now, the only industrial-class Optane storage drive mounts just 375GB of storage directly to a PCI express slot, and those drives are selling for thousands of dollars in bulk orders to corporate customers—not exactly a wise investment for a traditional independent system-builder.

According to Intel’s marketing material, adding an Optane M.2 memory module to a 7th-gen Core motherboard can speed up overall “performance” by 28%, with a 1400% increase in data access for an older, spinning hard drive design and “twice the responsiveness” of everyday tasks.

Clearly, this technology makes the most sense when paired with a spinner drive and the performance gains will be less dramatic if you already use an SSD as your main storage device. Optane modules are relatively cheap performance add-ons—approximately $50 for the 16GB M.2 card and $100 for the 32GB version, at the time of writing—it might seem like a no-brainer. But keep in mind a few things. One, you’ll need the latest seventh-generation processor and a compatible motherboard to take advantage of it. Two, though Intel is advertising performance boosts for more or less any situation and application, the most dramatic improvements come from a system with an older spinning hard drive, not increasingly-popular SSD storage. The Optane system also increases power draw by a considerable margin.

In conclusion the average PC enthusiast would be better off tossing his HDD for a high capacity SSD and saving the headache of upgrading his motherboard and processor in order to use Intel’s Optane Memory. However from Intel’s point of view the innovation is clearly a move to add more proprietary peripherals to their ecosystem of power-hungry jumbo-cache CISC processors that they can market to corporations and consumers alike.

No responses yet